Indonesian Proposal: Pay Us Not to Chop Down Our Trees

PAPUA, Indonesia -- Barnabas Suebu, the governor of this remote and wild province, recalls flying over parts of Indonesia a decade ago and being appalled by what he saw below. A major island in the archipelago, once home to massive virgin rain forests, had been stripped bare for development and plantations.

"I felt so sad," Mr. Suebu said. "This kind of damage must be avoided in Papua."

Until recently, similar destruction in Papua seemed inevitable. The Indonesian government has long wanted to hack through its rain forest to make way for agricultural development. In the past year, Chinese and Indonesian companies have unveiled plans to spend billions of dollars on huge palm-oil plantations, hoping to feed demand for biodiesel. Papua appeared on the verge of its first-ever investment rush.

In an interview in Papua's capital, Jayapura, Mr. Suebu, 61 years old, acknowledged that his impoverished province needs the economic boost development might bring. But rather than allow Papua to follow the same course as many other Indonesian islands, Mr. Suebu is trying to chart a new direction. In effect, he wants Papua to be paid not to cut down its rain forest.

His proposal: Have Papua become an active player in the world's emerging carbon markets -- a series of exchanges that let investors and companies buy and sell the right to pollute. By setting aside a portion of the earmarked land for conservation, he believes Papua could attract companies who wish to gain carbon "credits." These valuable commodities, traded on various types of exchanges, allow investors to offset their carbon-dioxide emissions elsewhere. Credits on the European Union's trading system are worth about $27 per ton of carbon dioxide.

The plan for Papua came to the governor's attention by way of Dorjee Sun, a 30-year-old Australian who became a millionaire developing Internet software. Under Mr. Sun's model for Papua, European and U.S. investors would put money into an offshore carbon fund. The money would then flow to local governments if they keep their promises not to cut forest land. In return, investors stand to receive credits based on how much carbon dioxide would have been emitted if the forests were burned. Compliance would be monitored via satellite technology.

If successful, the Papua approach could help influence anti-global warming efforts in Indonesia and elsewhere.

"We need to show Papua that there is an alternative to plantations," said Mr. Sun on a recent visit to the island. "This is the last frontier."

Rain forests play a key role in maintaining the world's environmental balance. Trees and plants soak up carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. Ancient forests store more than new plantations. Protecting them also means reducing one of the chief causes of harmful carbon-dioxide emissions: fires set to clear the forests for other agricultural purposes.

According to the World Bank, roughly 22 million acres of rain forests are lost globally each year when they are cleared by fire for alternate use. These fires account for about 20% of the world's carbon-dioxide emissions -- more than the total from all vehicles, airplanes and ships. Such fires make Indonesia the third-largest emitter of carbon dioxide after the U.S. and China -- even though it has the world's 22nd-largest economy.

Curbing forest destruction is gaining more attention as a strategy to combat global warming. The Kyoto protocol, the global treaty intended to cap emissions, allows companies to earn the right to pollute by funding emission-reducing projects in developing nations. Credits to pollute are traded around the world. Major buyers include heavy-emitting companies in Europe and Japan, which are subject to Kyoto-related emission caps.

Currently, the treaty allows companies to generate credits by planting new trees. But it doesn't cover efforts to preserve existing trees -- the sort of plan now being pursued in Papua. Even so, most of the Kyoto-sanctioned projects have focused on cutting pollution from industry; only one has involved planting trees.

But now, as diplomats begin debating a new international agreement to succeed the Kyoto Protocol when it expires in 2012, there's increasing talk of changing the rules to allow tree-preservation -- also dubbed "avoided deforestation" -- to produce emission credits that can be bought and sold.

Messrs. Sun and Suebu concede that their project is unlikely to interest companies that must meet official emissions-reduction targets under the current Kyoto treaty. But they believe change is afoot.

In December, the United Nations' Climate Change Conference will meet on the Indonesian island of Bali to discuss whether to include "avoided deforestation" projects in the successor treaty to Kyoto. At the meeting, the World Bank will detail its plan to spend $250 million over the next year in a pilot program to reward nations that protect their forests.

Even if Kyoto standards remain ironclad, Messrs. Sun and Suebu see potential.

They suspect that the Papua fund will also appeal to investors who want to get in on the growing number of unregulated, ad-hoc markets dedicated to the voluntary trade of carbon credits. These markets, including the Chicago Climate Exchange, sell different types of credits to companies that want to offset their carbon emissions -- sometimes going so far as to be "carbon neutral" -- for public-relations reasons. Some of these companies are in countries that have ratified Kyoto and want to go beyond what the treaty requires. Others are in countries that haven't ratified Kyoto and already permit avoided-deforestation credits.

"In my mind, we have to save the forests of Papua and make money from that," said Mr. Suebu.

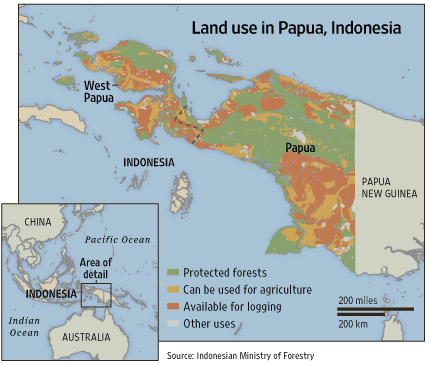

Still in the planning stages, the Papua project faces other hurdles -- starting with jurisdictional issues over who controls the land in question. Indonesia's powerful Forestry Ministry says it has the power to determine the fate of Papua's forests, a claim Mr. Suebu strenuously disputes.

And Messrs. Sun and Suebu have yet to calculate how much, financially, Papua would benefit from the project. Specific figures won't be determined until more scientific analysis is performed on the land and its carbon stash.

Many global warming experts say paying governments to protect forests needs to become part of the arsenal to stop climate change. Papua's plan could offer an attractive alternative for countries such as Brazil and the Democratic Republic of Congo that have huge tropical rain forests but need substantial investment.

Mr. Suebu has proposed to protect more than half of the Papua land targeted for development to see if such a plan can work. In the meantime, he has applied heavy brakes to the plantation companies' expansion aims, so far refusing to grant them permission to proceed with their planned developments.

The plantation companies in Papua aren't giving up, however. The only four-star hotel in Jayapura is swarming with Malaysian and Indonesian plantation executives hoping for an audience in the governor's mansion. The companies are proffering large investments in roads and ports and the creation of local jobs -- attractive incentives to the province's 2.5 million residents.Many people here still hunt wild animals for food and 40% live on less than $14 a month, according to the World Bank.

The companies may yet persuade Mr. Suebu to free up huge tracts for development, especially if Mr. Sun's plan fails to get off the ground. Even if the plan does take off, Mr. Suebu may decide to allow a mix of plantations and preservation to reap the maximum economic benefit.

Papua is the size of California and takes up the western half of the giant island of New Guinea. (The other half is the separate country of Papua New Guinea.) Indonesian Papua is almost entirely covered by vast stretches of virgin rain forests. Its central mountain range is capped by glaciers. The only large development in the province is a copper and gold mine owned by Phoenix-based Freeport-McMoran Copper & Gold Inc.

Mr. Suebu, a large man quick to break into a broad smile, was born on a small island on a lake near Jayapura. After law school, he founded a business conducting surveys for public-works projects. He became a member of the political party of Indonesia's former president and strong man, Suharto. In 1988, he was appointed Papua's governor.

After Mr. Suharto's fall in 1998, Mr. Suebu moved to Jakarta as an advisor to the president's successor, B.J. Habibie. Shortly after, Mr. Suebu was appointed Indonesia's ambassador to Mexico, where he learned how nations such as Costa Rica were earning money from protecting forests. A decade ago, Costa Rica was a pioneer of so-called debt-for-nature swaps in which developed countries wrote off loans made to the republic in return for specific forest conservation measures. "I thought, 'This is great' because here you protect the forest but money still comes in," Mr. Suebu said.

He returned to Indonesia in 2002, becoming an adviser to the World Bank. In July 2006, he was elected governor, the first time the post had been filled by popular vote.

On taking office, Mr. Suebu pledged the local government would make decisions about Papua's forests -- not the central government in Jakarta.

The governor's powers had changed dramatically from his earlier stint in the job. A 2001 law granted a large degree of autonomy to Papua, including greater say over how forests and other natural resources are parceled out to investors. It also gave the provincial government 80% of the revenues from natural-resource-based industries such as mining and forestry -- a gusher of cash that has allowed Mr. Suebu to hand out $10,000 to every village in the province.

But a few weeks into his tenure, Mr. Suebu says he was called to Jakarta by Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. Mr. Yudhoyono explained how the government hoped to attract billions of dollars in investment and create 3.5 million jobs in the country from developing plantations of oil palms, cassava and sugar cane -- the raw material for biofuels.

The Forestry Ministry, which argues it still has the final authority over Papua's forests, had in 1999 earmarked land roughly the size of Portugal for agriculture. The president asked Mr. Suebu to immediately open up two million acres of those for conversion to plantations. Plantation companies from Indonesia to Malaysia were running out of space elsewhere in the country and wanted to expand to the island.

Mr. Suebu balked. In the past, he says, small-scale palm-oil ventures in Papua have cut down and exported valuable tropical hardwood but, in many cases, failed to develop plantations on the cleared land. In other cases, workers on the plantations were brought in from Indonesia's main island of Java, sparking social conflict with locals.

Mr. Suebu balked. In the past, he says, small-scale palm-oil ventures in Papua have cut down and exported valuable tropical hardwood but, in many cases, failed to develop plantations on the cleared land. In other cases, workers on the plantations were brought in from Indonesia's main island of Java, sparking social conflict with locals.

Papua's forests in the past several years also have become a rallying point for environmentalists as Indonesia's other virgin forests disappear. The country has the world's fastest rate of deforestation, losing an area the size of Belgium annually. In provinces such as Kalimantan and Sumatra, the U.N. estimates that lowland forests will be wiped out by 2022, putting the survival of species like orangutans and elephants at risk. Mr. Suebu didn't want Papua to be next. "We're not doing that," he said he told the president.

But the pressure on him only increased. The government of Malaysia, the world's largest palm-oil producer, invited Mr. Suebu to see for himself how plantations can spur economic growth. Then, in January, Indonesia's central government said it had signed preliminary deals to develop biofuel projects worth a combined $12.4 billion.

China National Offshore Oil Corp. and its Indonesian partner, Sinar Mas Agro, announced they had agreed with Jakarta to invest $5 billion over eight years to develop palm-oil plantations in Papua.

That same month, Mr. Sun, the carbon-trading proponent, made his first trip to Indonesia from Australia to discuss how to counter the threat from plantations.

In Indonesia, Mr. Sun met LeRoy Hollenbeck, an American adviser to the governor of Aceh, an Indonesian province at the other end of the country from Papua. The governor, Irwandi Yusuf, was looking for ways to make money by protecting forests. Mr. Sun offered to use his business expertise to raise money for a carbon fund that would pay for preservation. Mr. Hollenbeck, who had known Mr. Suebu since the 1980s, approached Papua's governor to see if he would be interested in joining the effort. Mr. Suebu said yes.

In April, the two governors held a summit in Bali, backed by the World Bank. In a formal declaration, they offered to stop forest destruction, and called on the global community to step up with financing. Mr. Suebu agreed to protect three million acres for carbon trading from the land Jakarta wants to convert to agriculture. That could rise to 12 million acres if the initial carbon-trading plan is successful, he said.

Soon after the Bali declaration, Mr. Sun bought a controlling stake in the Carbon Pool Pty. Ltd., a small Australian company that in 2006 did one of the world's first avoided-deforestation trades. In that project, Carbon Pool bought out farmers' rights over 30,000 acres in Queensland, in the northeast of Australia, and sold the resulting carbon credits to Anglo-Australian mining company Rio Tinto Ltd. The terms of the deal were not disclosed.

Soon after the Bali declaration, Mr. Sun bought a controlling stake in the Carbon Pool Pty. Ltd., a small Australian company that in 2006 did one of the world's first avoided-deforestation trades. In that project, Carbon Pool bought out farmers' rights over 30,000 acres in Queensland, in the northeast of Australia, and sold the resulting carbon credits to Anglo-Australian mining company Rio Tinto Ltd. The terms of the deal were not disclosed.

Mr. Sun hopes to get Rio Tinto to invest in his new venture for Papua and Aceh. Rick Humphries, head of climate-change strategy for Rio Tinto's aluminum division in Brisbane, says the company is "keen to look at other opportunities" in forest-protection projects, but didn't specifically comment on Papua.

In July, Mr. Sun traveled for the first time to Papua for a meeting with Mr. Suebu in which they discussed strategies for selling the Papua fund. Mr. Sun then flew directly to the U.S. to hold preliminary meetings with investors, including hedge funds, companies and rich individuals, he says. He declines to release a tally of the fund-raising efforts